Nurse, pass me that meat hook ....

This amazing newspaper report in Nottingham Evening Post of 5 August 1927 of an operation at sea in harrowing conditions captured my attention (full transcription follows) and I wondered who this admirable young doctor was, as well as his able lady assistant. (Merchant navy crewmen are notoriously difficult to trace so I already knew the likelihood of of finding anything on the patient and the cook would be minimal.)

|

| British Newspapers Archive |

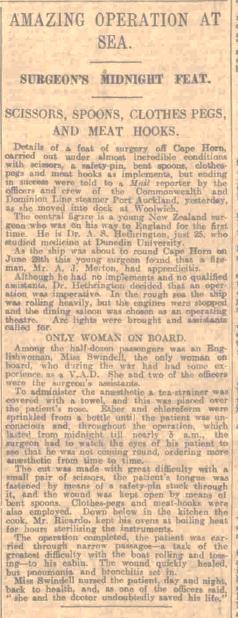

SURGEON'S MIDNIGHT

FEAT.

SCISSORS, SPOONS,

CLOTHES PEGS, AND MEAT HOOKS.

Details of a feat of

surgery off Cape Horn, carried out under almost incredible conditions with

scissors, a safety-pin, bent spoons, clothes-pegs and meat hooks implements,

but ending in success were told to Mail reporter

by the officers and crew of the Commonwealth and Dominion Line steamer Port

Auckland, yesterday, as she moved into dock at Woolwich.

The central figure

is a young New Zealand surgeon who was on his to England for the first time. He

is Dr. A. S. Hethrington, just 25, who studied medicine at Dunedin University.

As the ship was about

to round Cape Horn on June 28th this young surgeon found that a fireman, Mr. A.

J. Merton, had appendicitis.

Although he had no

implements and no qualified assistants, Dr. Hethrington decided that an

operation was imperative. In the rough sea the ship was rolling heavily, but

the engines were stopped and the dining saloon was chosen an operating theatre.

Arc lights were brought and assistants called for.

ONLY WOMAN ON BOARD.

Among the half-dozen

passengers was an Englishwoman, Miss Swindell, the only woman on board, who

during the war had had some experience as a V.A.D. She and two of the officers

were the surgeon’s assistants.

To administer the

anaesthetic, a tea-strainer was covered with towel, and this was placed over

the patient’s nose. Ether and chloroform were sprinkled from a bottle until the

patient was unconscious and, throughout the operation, which lasted from

midnight till nearly 3 a.m., the surgeon had to watch the eyes of his patient

to see that he was not coming round, ordering more anaesthetic from time to

time.

The cut was made

with great difficulty with a small pair of scissors, the patient’s tongue was

fastened by means of safety-pin stuck through it, and the wound was kept open by means of bent spoons. Clothes-pegs and meat-hooks were also employed. Down

below in the kitchen the cook, Mr. Ricardo, kept his ovens at boiling heat for

hours sterilising the instruments.

The operation

completed, the patient was carried through narrow passages—a task of the greatest

difficulty with the boat rolling and tossing—to his cabin. The wound quickly

healed, but pneumonia and bronchitis set in.

Miss Swindell nursed

the patient, day and night, back to health, and, as one of the officers said, “she

and the doctor undoubtedly saved his life.”

After reading this a couple of times, it does raise a few questions. Amazing as the feat is, how was it that the young doctor had to resort to such basic hardware in the first place?

Commonwealth & Dominion Line (later Port Line) was a major shipping company of the day and even if the young doctor did not have his own personal fully-equipped medical bag, surely there would have been a mandatory stock of medical items on board? There was obviously ether and chloroform to hand, so why none of the other necessary instruments? A bit of a mystery not explained in this or any of the other similar newspaper reports.

|

| SS Port Auckland, c.1924 Australian Maritime Museum |

|

| Every doctor would have carried a bag similar to this (scalpel case on right) Doctor's Bag c. 1890-1930, London Science Museum |

And as to the leading players in this drama, I soon discovered that there was a slight misprint in the doctor's name, he wasn't A.S. but was in fact Dr. Owen Stanmore Hetherington, born in Thames, New Zealand, on 3 April 1903.

Extensive references can be found to Dr. Hetherington in the New Zealand newspaper and other archives. In 1930, he was married to Janet Brown Dickson in England and then was in private practice in his home town of Thames until 1939 when he enlisted in the NZ Army medical corps.

He saw action in Greece, and made his escape and hid out for three weeks before being taken prisoner in Crete. He served in a hospital in Athens that was staffed largely by British personnel but run by the Germans. He was later sent to Germany to serve out the rest of the war in a POW camp, where his experience in operating with limited instruments must have served him well. He was awarded an MBE when repatriated in 1944. He died in Auckland on 18 October 1958. (This series of newspaper cuttings from Papers Past New Zealand)

(It is interesting to find in the ship records that after the events of 1927, in 1930 Dr. Hetherington was back at sea and listed as the ship's surgeon on a voyage on the cargo ship Talthybius from Hong Kong to Seattle where his nationality is shown as "Irish", presumably because the clerks had little experience of the New Zealand accent! A few weeks later he is found arriving from New York into the UK on the White Star Liner, Cedric, but this time he listed as a passenger rather than the ship's surgeon.)

-o0o-

And so to the doctor's assistant in this drama - Miss Swindell - who turns out to be Mary Elizabeth ("Bessie") Swindells and, as has happened with some of my other spontaneous genealogical investigations, I have been astonished to discover that it is possible a member of my own family may have met Bessie Swindells!

Bessie was born on 24 November 1887 in Shrewsbury, Shropshire. Her father was Henry Price Swindells, who would become the Manager of the Aire & Calder Canal Navigation Company. Her mother was born Kate Jane Kendrick, and Bessie had one brother, Henry Kendrick Swindells.

She never married, but must have had some nursing training when she signed up as a VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) during World War I. Although I have been unable to find her card through the Red Cross VAD records, the Cheshire Observer reports that for much of the War she was based in the hospitals on the island of Malta ... and it is here where my own aunt served as a VAD as well so there is every chance she could have encountered Bessie either in her day-to-day work or during their time off.

The Swindells family were much connected with heavy industries such as milling as well as canal transport, and it appears from various records that Bessie lived with family members and did not work as she had private means. Apparently she had been living for a while in New Zealand prior to taking that voyage where her WW1 nursing experience came in useful. She died in her 100th year, on 12 April 1988 in Poole, Dorset, and left an estate in excess of £55,000.

This image is from a public family tree on Ancestry and is stated to be of Mary Elizabeth Swindells. From the 1920s fashion, it probably dates to just before or after she helped Dr. Hetherington in the operation.

|

| Ancestry.co.uk |

Comments

Post a Comment